As obvious as it may seem, every PhD project needs constraints: this mantra extends even to the apparently-arcane field of ‘medieval French literature’. At first glance, the alterity of the field, both in its temporal distance from us and in its language, may appear to suffice in this respect: surely ‘it’s medieval, and it’s in foreign’ will narrow the field down sufficiently? Of course, medieval French literature is still an impossibly broad field to ‘cover’ in one (or even one hundred) PhDs.[1] In reality, as any medievalist knows, the discipline of ‘medieval French literature’ is home to a vast range of texts which are in many ways more different than they are alike.

With this in mind, I needed a second set of constraints when devising my proposal. Last week, I looked at two of these, in the form of the phrase ‘didactic literature’. This week, it’s time to tackle what is perhaps an even thornier topic: ‘Anglo-Norman’. In a way, it’s perhaps surprising that I’ve waited for so long before addressing this subject: it is, after all, the source of the terrible pun that serves as my blog’s title. In my defence, I’d like to point out that it’s not an easy topic to tackle: the word ‘Anglo-Norman’ is deceptively complex.

In the broadest possible sense, Anglo-Norman as a word can be both a noun and an adjective. The adjective ‘Anglo-Norman’ is, to use Susan Crane’s terminology, a ‘political and geographic (term), designating persons united by place and time rather than by dialect.’[2] That particular ‘place and time’, for our purposes, is England in the centuries following the Norman Conquest in 1066 and in reference to members of the ‘dominant culture’;[3] hence its use in article titles such as ‘The Anglo-Norman civil war of 1101 reconsidered’. To be ‘Anglo-Norman’, then, is to have a stake in England after the Conquest.

One of the strongest markers of involvement in this social class, of course, was language. Just as we can refer, somewhat awkwardly, to ‘French French speakers’, it would be grammatically correct to describe the Anglo-Norman gentry as speaking the language of ‘Anglo-Norman’. The term ‘Anglo-Norman’, however, is a linguistic red herring. Its status as a compound noun might lead us to consider it as a sort of linguistic fusion between the ‘Norman’ of William’s conquerors and the ‘English’ of the Saxons, but in fact the language itself is rather different. As Ian Short emphatically puts it in the very first sentence of his monumental Manual of Anglo-Norman, ‘Anglo-Norman is a full and independent member of the extended family of medieval French dialects (…) it is the name traditionally given to the variety of medieval French used in Britain between the Norman Conquest and the end of the 15th century.’[4] Various alternative terms have been proposed in order to circumvent this semantic slipperiness, among them ‘Anglo-French’ and ‘insular French’. One alternative in particular, that of ‘the French of England’, has recently given its name to a research group and to an attendant translation series. Whatever term we use, though, its influence on modern English is palpable even today: to give the canonical example, it is the reason why English has multiple words for many objects, such as the French-inspired ‘beef’ (< boeuf) alongside the Saxon ‘cow’.

That is not to say that this ‘French of England’ imposed itself completely on the population, dominating the English language and taking no cues from it at all: to state the obvious, French (a term used by Anglo-Norman writers) is today, as the latest A-Level figures show, seen as resolutely ‘other’. One of the most fascinating aspects of the Anglo-Norman language is its status as part of a ‘triglossia’ with English and Latin, and lexical borrowings from English did occur. One of the earliest extant Anglo-Norman texts, the Voyage of St. Brendan, uses the term raps (ropes) in what appears to be a straight borrowing (with morphological assimilation) from English. More subtly, the term lodmanage, referring to the navigation of a ship, has been identified as deriving from the Middle English lodman, with a French suffix (-age) attached.[5]

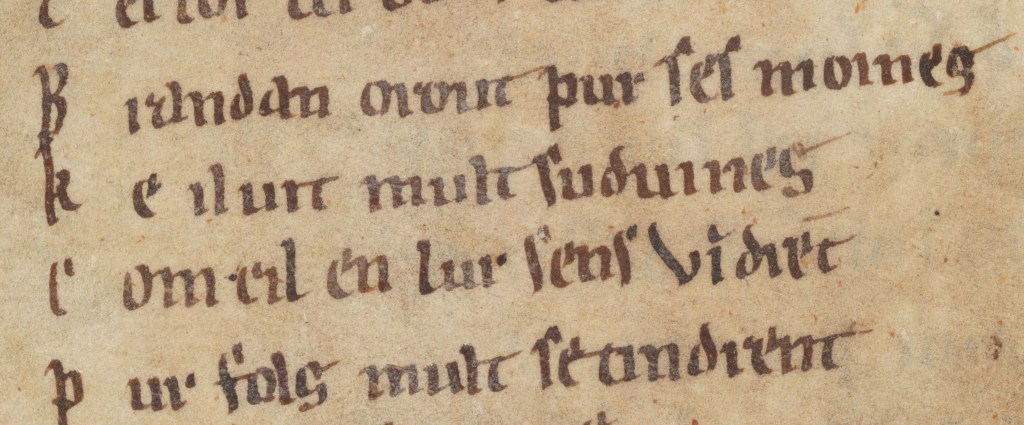

When you read Anglo-Norman, though, you definitely have to read it with your ‘French hat’ on. Let’s return to the extract from the Voyage for an example:

Dist li abes : « Ne vus tamez, / Mais Damnedeu mult reclamez ! / E pernez tut nostre cunrei, / Enz en la nef venez a mei ! » / Jetet lur fuz e bien luncs raps …

Do not be afraid,’ said the abbot, ‘but pray fervently to God, take all our affairs, and join me on the boat!’ He threw them poles and long ropes.[6]

Anglo-Norman is undeniably French. From lexical elements – pernez for ‘prendre’, jetet for ‘jeté‘, and venez for, well, ‘venez’ – to broader syntactic points, it’s clear that we’re dealing with a distinctive, but easily-identifiable, variety of a language that, during the Middle Ages, extended far beyond the borders of what we today call ‘France’. It’s this multiplicitous nature of Anglo-Norman – the linguistic ambiguity; the questions of social class and status that it brings with it – that makes it so exciting for me. You won’t be surprised to learn, then, that I can’t wait to get stuck into some more Anglo-Norman come September.

1 On this topic, Simon Gaunt has (amongst others) made the valid point that all three of these terms ‘medieval’, ‘French’ and ‘literature’ ‘raise(s) a number of important preliminary problems’ of definition and meaning. In a sense, then, ‘medieval French literature’ is not merely insufficiently specific as a constraint, but also creates more problems than the convenient appellation solves! For a stimulating discussion of each of these terms in turn, see Simon Gaunt, Retelling the Tale: An Introduction to Medieval French Literature (London: Duckworth, 2001), pp. 9-16.

2 Susan Crane’s introduction to the various meanings and evolutions of the term ‘Anglo-Norman’ is, of course, far more comprehensive and well-researched than anything I write could ever hope to be. See Susan Crane, ‘Anglo-Norman Cultures in England, 1066-1460’, in The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 35–60. (That particular quote is on p. 44.)

3 Ian Short, Manual of Anglo-Norman (London: Anglo-Norman Text Society, 2007), p. 11.

4 Short (2007), p. 11. Short also brings together (and compares) many of the alternatives to the term ‘Anglo-Norman’ listed above.

5 For more on this second example, see the wonderful ‘Medieval Bilingual England’ website.

6 Ian Short and Brian Merrilees (eds.), Le Voyage de Saint Brendan, Champion classiques du Moyen Âge, 19 (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2006), ll. 457-61 (my translation). If you’re wondering, they’re having a bit of a panic, and with good reason: the ‘island’ on which Brendan et al have just moored has turned out in fact to be a whale.

Cover image: a detail from one manuscript of the Voyage of St. Brendan (ll. 815-18). Cologne, Fondation Martin Bodmer, Cod. Bodmer 17, fol. 1r.

Leave a comment